Fewer Cases Are Getting Leave to Appeal to the Supreme Court of Canada. Why?

As many readers of our blogs know, we maintain a database that contains a wealth of information about every Supreme Court of Canada leave application decided from January 1, 2018 onward. That dataset allows us to provide a range of analysis and predictions relating to Supreme Court leave applications. But there is one fact that is apparent to all Supreme Court watchers that you don’t need a rich dataset to know: far fewer cases than usual got leave to appeal to the Supreme Court in 2022. The question this blog post tries to answer is: why?

For many of us watching the Supreme Court, this drop in successful leave applications is an unfortunate development. Fewer leave applications granted means less new law from the Supreme Court, particularly in civil cases where there are no appeals as of right. For litigators, this means fewer opportunities for the Court to advance the law and resolve outstanding issues.

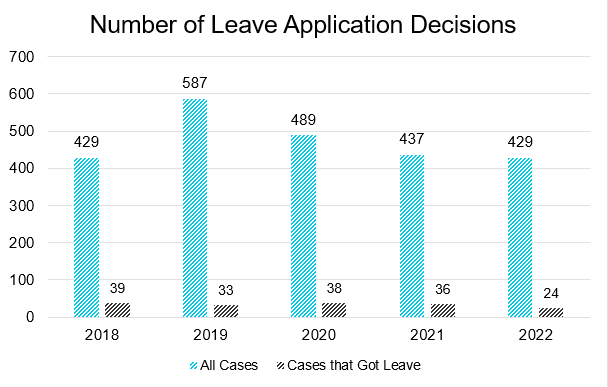

Let’s start with some basic information about the drop in successful leave applications. In 2022, the Supreme Court of Canada granted leave to appeal in just 24 cases. This is a substantial drop compared to the prior four years, which saw anywhere between 33 and 39 cases get leave.

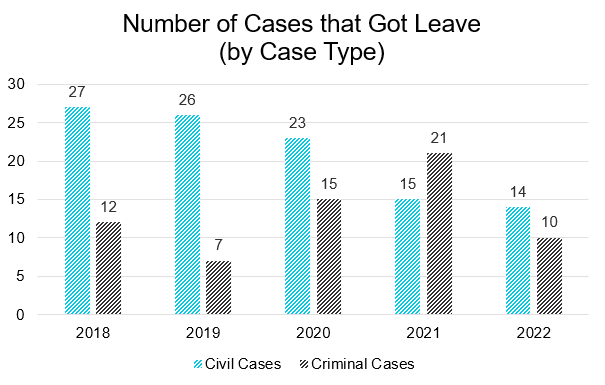

The drop in successful leave applications is particularly notable in civil cases (which we define for present purposes to be any non-criminal cases). Just 14 civil cases got leave to appeal in 2022, continuing a general downward trend. While fewer criminal cases also got leave than has been the average over the last several years, the trend is not nearly as pronounced.

This data clearly shows the drop in leave applications in 2022, but again, the real question is why. There are at least three potential explanations for why there might be fewer successful leave applications in any given year:

- The first explanation is that there were simply fewer leave applications made than in prior years, which in turn reduced the pool of cases from which leave applications could be granted.

- The second explanation is that the leave applications were, on average, less “leave-worthy” than in previous years. That is, cases were less likely to raise issues of public importance than in prior years.

- The third explanation is that the Supreme Court got stingier in granting leaves. That is, the Court was less likely to grant leave to a case, all things being equal, than they would have been in prior years.

Distinguishing between these three explanations is important to understanding whether it is actually a problem that the Supreme Court granted fewer leave applications. If the reason for fewer leaves being granted lies in either explanations 1 or 2, then arguably there is little cause for concern. Even those who lament the low number of leaves granted would agree that the Court should only be granting leave and engaging with a case if it raises a genuine issue of public importance. Put differently, there is no point in the Court granting leave in cases just to increase the number of cases it hears; the cases should be ones that can meaningfully advance or clarify the law. By contrast, if the reason for fewer leaves being granted lies in explanation 3, then that may suggest that the Court has cases available to it, but is merely deciding to take fewer opportunities to advance the law than it once did.

While these are difficult questions to answer definitively, analytics that we conducted on our dataset provided some insight into these questions.

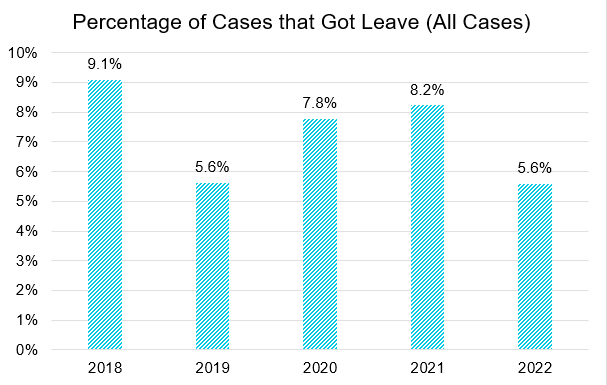

Our data allowed us to largely reject the first potential explanation. While there were slightly fewer leave applications decided in 2022 than in 2020 or 2021, the data showed that the percentage of cases that got leave was down significantly in 2022 compared to past years.

While the percentage of cases that got leave in 2022 was comparable to the percentage in 2019, 2019 was an abnormally high year in terms of number of leave applications decided (587 leave applications decided, compared to less than 500 in every other year in our dataset). That in turn resulted in an abnormally low rate of leave applications granted in 2019, despite a much higher number of leaves granted (33) than in 2022.

Consequently, the data seems to fairly definitively show that the low number of successful leave applications in 2022 is not an overall pipeline problem, in the sense that materially fewer leave applications were before the Court. Rather, the explanation instead must be that the low number of successful leave applications in 2022 is a function of either a change in the types of cases in which leave is sought, or a change in the Court’s approach to leave applications.

While distinguishing between those two explanations is challenging, our analysis provides some support for the latter explanation. That is, the Supreme Court was simply less inclined to grant leave to any particular case in 2022 than it would have been in prior years.

We say that for two reasons.

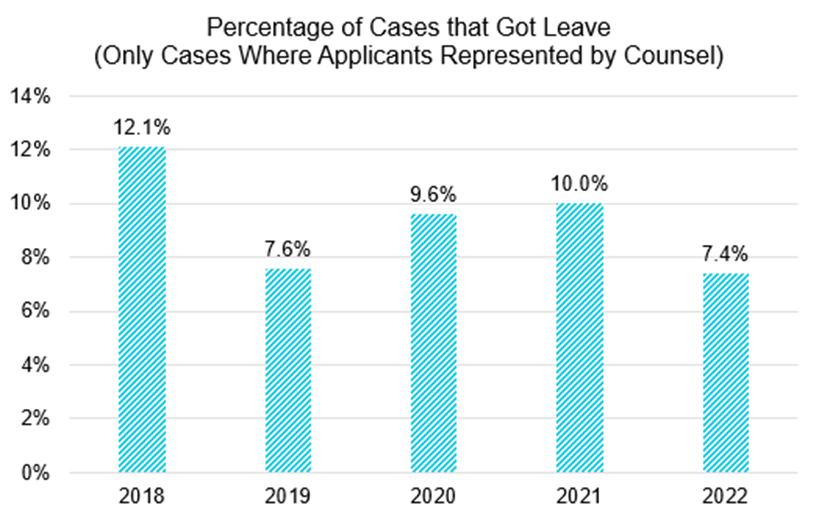

The first reason is that our analysis shows little difference between 2022 and prior years in terms of the prevalence of some of the most salient factors associated with getting leave or not. Take for example the presence of self-represented litigants. Our data shows that leave applications in which the applicant is self-represented are extremely unlikely to be successful. In our dataset, despite approximately one-fifth of leave applications being brought by a self-represented litigant, there was not a single leave application in which a self-represented litigant was granted leave. Consequently, if, for example, there were a significant spike in the percentage of leave applications filed by self-represented litigants in 2022, it might not be surprising to see a lower rate of leave applications being granted in 2022.

Our data shows no significant spike in the percentage of leave applications brought by self-represented litigants. In 2022, approximately 24% of leave applications were brought by self-represented litigants, which is roughly the same percentages as in 2018 and 2019, and only a modest increase of 5-6% percentage points higher than in 2020 and 2021.

Our data shows that this relatively modest change in the number of self-represented applicants in 2022 compared to 2020 and 2021 is not what has driven the lower number of leave applications. The graph below shows the percentage of successful leave applications only in cases where the applicant is represented by counsel. That graph shows that even after controlling for any increase in the proportion of applications by self-represented litigants, the percentage of cases in which the Court granted leave in 2022 was still materially down over previous years.

The second reason we believe that the Supreme Court was simply less inclined to grant leave in 2022 comes from a more sophisticated multivariate analysis of the factors correlated with seeking leave. Using a statistical technique known as a logistic regression model, we can isolate the impact of various factors on the likelihood of a particular case getting leave to the Supreme Court. Using that approach, we calibrated a series of models that included the factors that we know have an impact on the probability of getting leave to appeal, and we also added in what is called in statistical terms a “dummy” variable that reflects whether a case was decided in 2022 or not. Put differently, including this 2022 “dummy” variable in the model allows us to estimate whether, after controlling for other factors, a case decided in 2022 was less likely to get leave than a case decided in prior years, merely because of the fact that it was decided in 2022. (We previously used a similar statistical method to find that there was no evidence that the COVID-19 pandemic made it harder to get leave to appeal in our blog post here.

Our results provide support to the theory that it was simply harder to get leave in 2022, after controlling for other factors. We ran a series of models with different variables included, and in almost all of the models we ran, the dummy variable for 2022 was statistically significant at either the 90% or 95% levels. (In only one model we ran with a very large number of variables, the dummy variable just barely failed to meet the 90% threshold for statistical significance.) While not definitive, these results provide support for the notion that if two identical cases were before the Court, one in 2021 and one in 2022, the Court would have been less likely to grant leave in 2022 than in 2021.

As always, we should be cautious about overstating the inferences to be drawn from these results. No statistical model is perfect, and our model cannot account for every possible factor that might impact the probability of getting leave. It might be that 2022 was simply a different year in terms of features of cases that our model does not take into account. Moreover, the sample size of leave applications decided in any given year is not particularly large, and the dataset is unbalanced (meaning that getting leave is a relatively rare event, and the vast majority of cases in our dataset do not get leave). A relatively small number of cases annually in which leave is granted limits our ability to draw statistically significant conclusions.

All that being said, our analysis provides some reason to think that there was a shift in the Supreme Court in 2022 that made it harder to get leave than it was in previous years. It remains to be seen whether these trends will continue. If 2022 was simply an aberration, there is little cause of concern. But if these trends continue and the Court continues to grant leave to relatively few cases, there will be significant areas of the law that will advance relatively slowly.