Appeals to the Supreme Court of Canada: 2025 Year in Review

A few weeks ago, we shared an overview of trends in the Supreme Court of Canada’s leave decisions in 2025. In this post, we follow that up with a look at trends in appeals decided by the Supreme Court of Canada over the last year.

The analysis in this post relies on the data from our recently updated Supreme Court of Canada Appeals dataset.

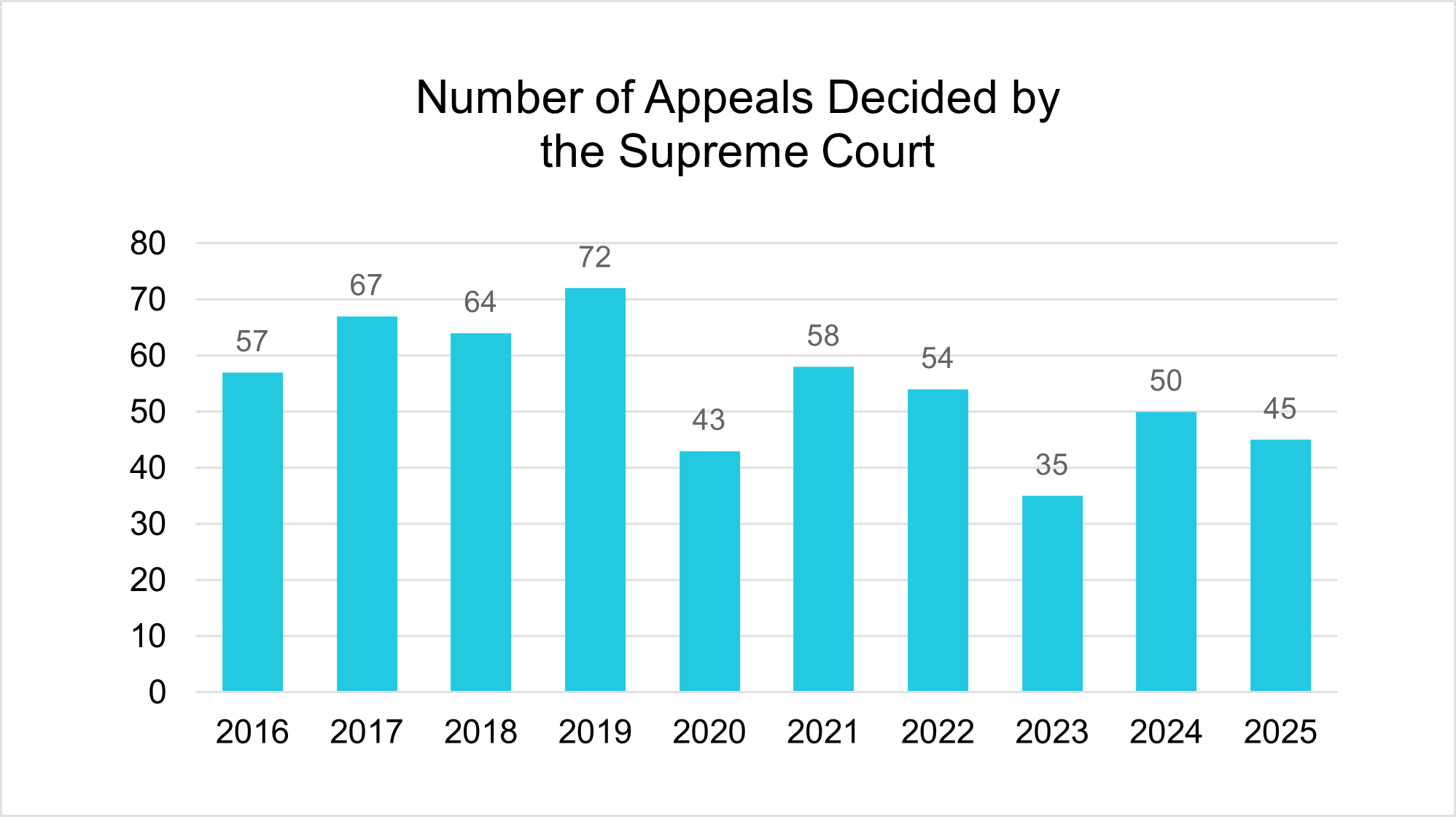

1. The Supreme Court’s Docket Remains Historically Small

In 2025, the Court decided 45 appeals. Before 2020, the Court routinely decided 50 to 70 appeals per year. Since 2020, that number has collapsed. The low point was 35 appeals in 2023.

While 2025 represents a modest recovery from that trough, it still reflects a new, lower post-pandemic normal. The Supreme Court of Canada is now deciding roughly one-third fewer appeals per year than it did in the pre-COVID era. That matters because fewer appeals mean fewer opportunities for the Court to shape the law across the country.

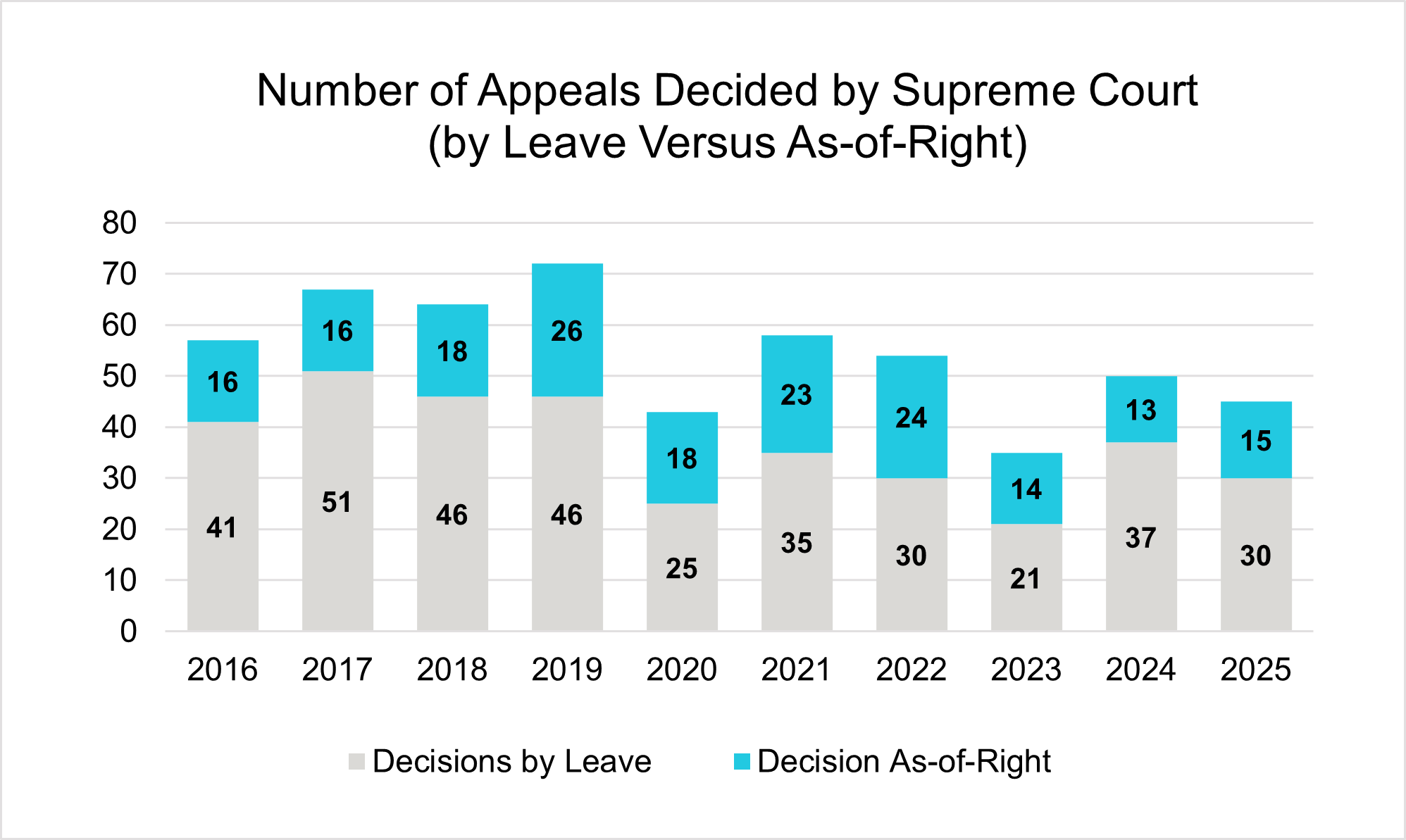

2. One Third of the Court’s Work is Now Mandatory As-of-Right Appeals

Of the 45 appeals decided in 2025:

- 15 were “as-of-right” appeals

- 30 were in cases where the Court had granted leave

That means one third of the Court’s docket consisted of cases it was required to hear rather than cases it chose to hear. That ratio is broadly consistent with recent years.

But when the total docket shrinks, the consequence is stark: the Court has less and less discretionary capacity to select jurisprudentially important cases.

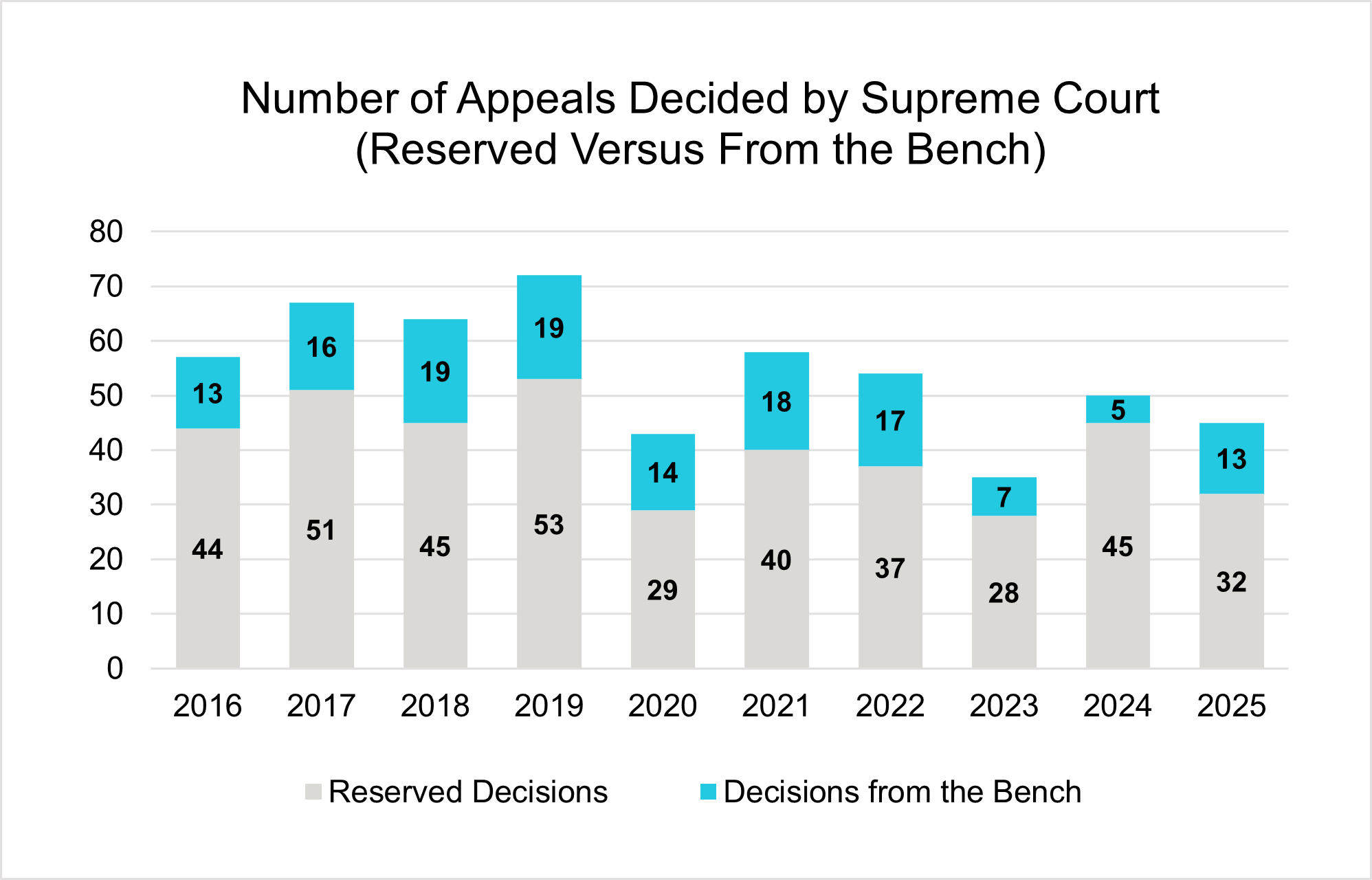

3. More Decisions From the Bench, Fewer Reasons That Develop the Law

In 2025:

- 13 appeals were decided from the bench

- 32 were reserved and released later with written reasons

That makes 2025 the third-lowest year for reserved decisions over the last decade, surpassed only by:

- 2020 (29 reserved decisions, the first pandemic year)

- 2023 (28, the modern low-water mark)

Decisions from the bench are fast and efficient. However, as we previously described in a paper I co-authored for the Supreme Court Law Review, they do not generate the kinds of detailed reasons that develop doctrine, clarify standards, or guide lower courts. Combined with a smaller docket, this means the Court is producing less jurisprudential output per year than at any point in recent history.

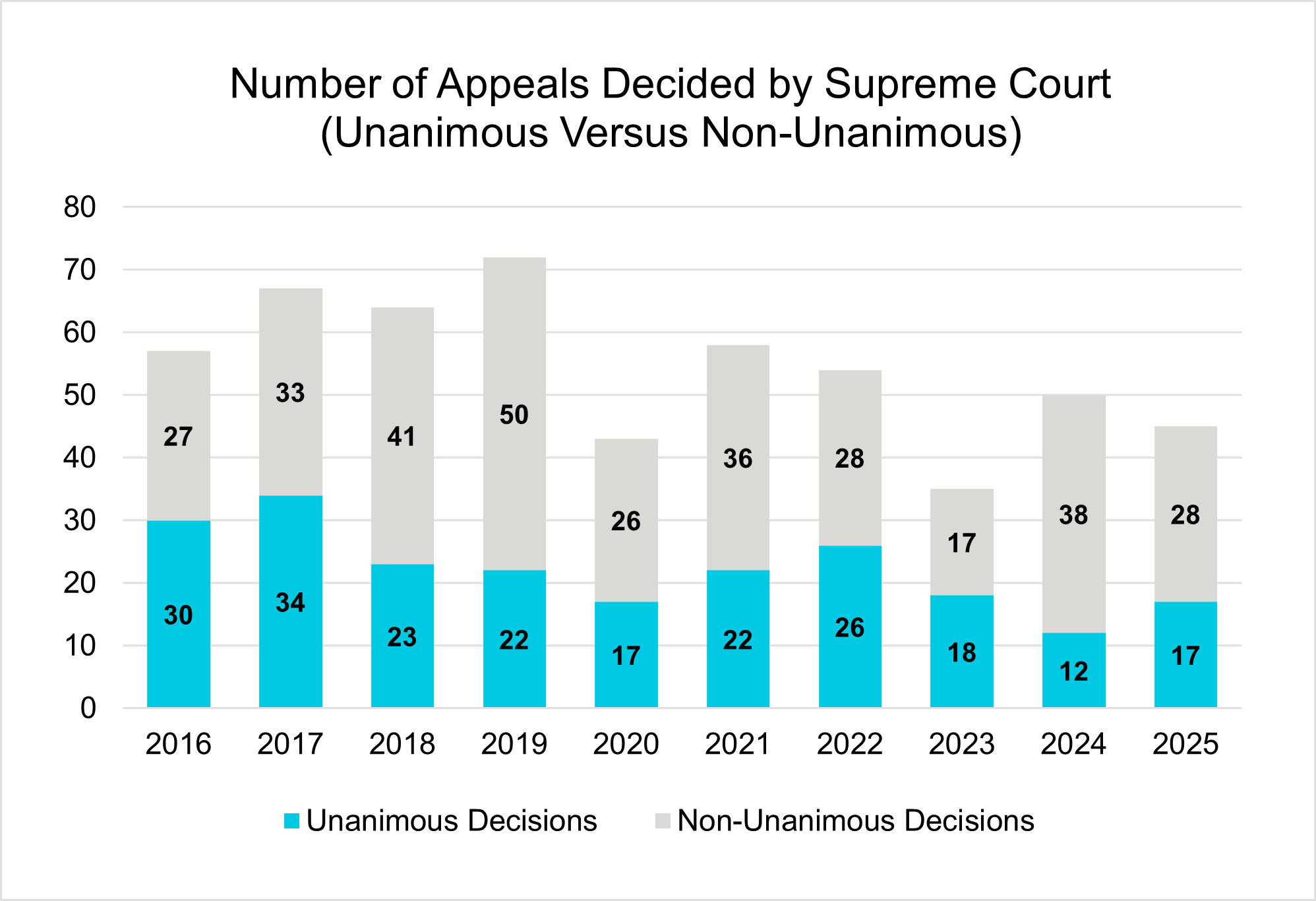

4. The Court Remains Sharply Divided

Only 17 of 45 appeals (38%) were unanimous. That means 62% of the Court’s decisions included at least one concurrence or dissent.

Even more striking: eight of the 45 appeals (18%) were decided by a single vote. These figures are not unprecedented in isolation, but they continue a structural shift away from the highly cohesive Court of the 2000s and early 2010s.

In a prior article I co-authored in the Supreme Court Review, my co-author and I documented a decline in voting agreement beginning in the mid-2010s. The 2025 data shows that trend continuing. The modern Supreme Court is not a fractured court, but it is no longer a tightly unified one either.

5. Criminal Law Dominated the Docket

This is the most striking result in the data.

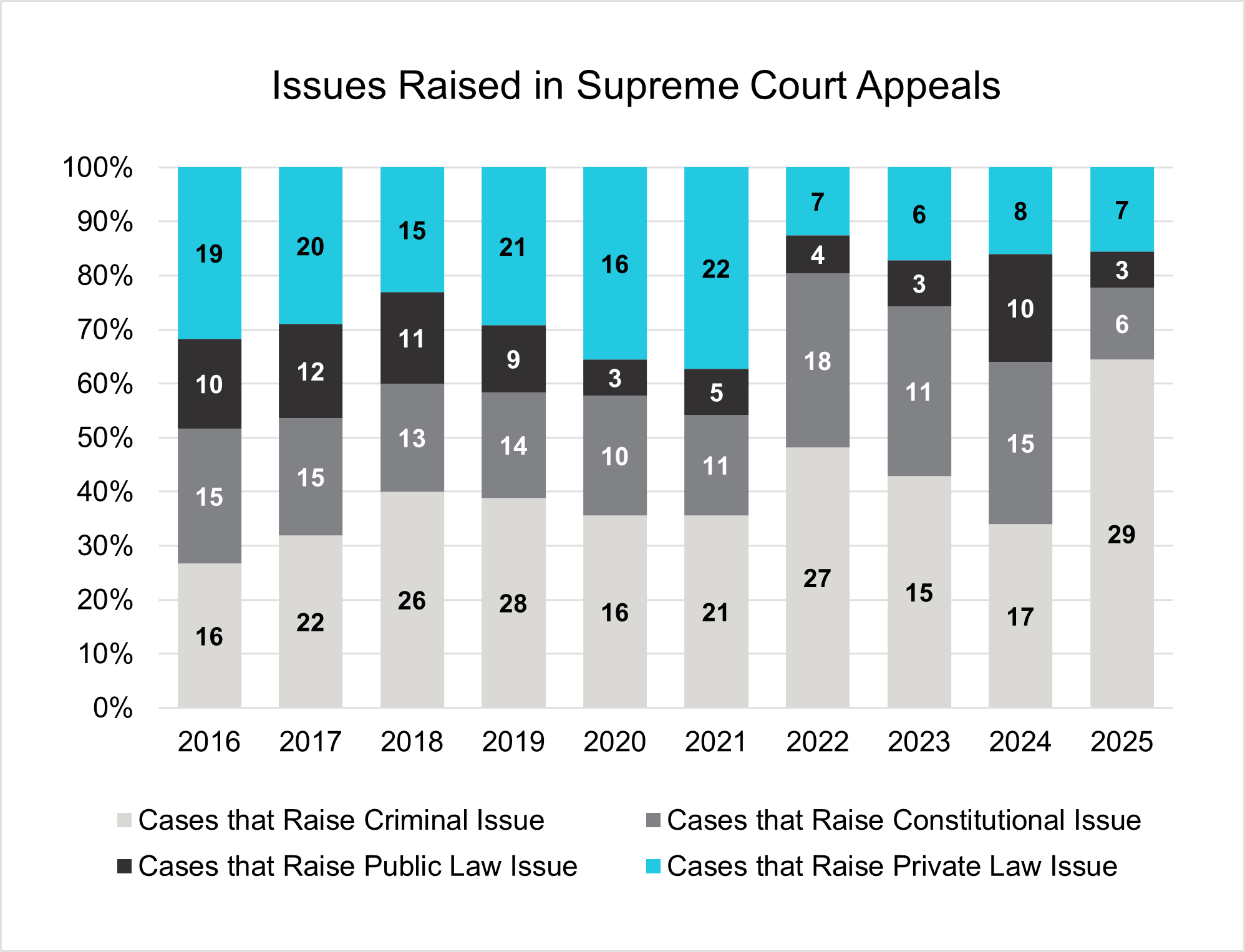

We coded every issue raised in 2025 appeals into four categories:

- Criminal (non-constitutional)

- Constitutional

- Public law (non-constitutional)

- Private law

29 out of 45 cases (64%) in 2025 raised a criminal law issue compared to just six that raised a constitutional issue, three that raised a public law issue, and seven that raised a private law issue. More than 60% of all issues before the Court in 2025 were criminal, non-constitutional matters.

Over the past decade, criminal non-constitutional issues usually accounted for less than 40% of the Court’s work, and never more than 50%. 2025 was an outlier. The Supreme Court has always been a major criminal law court; in 2025, it was overwhelmingly so.

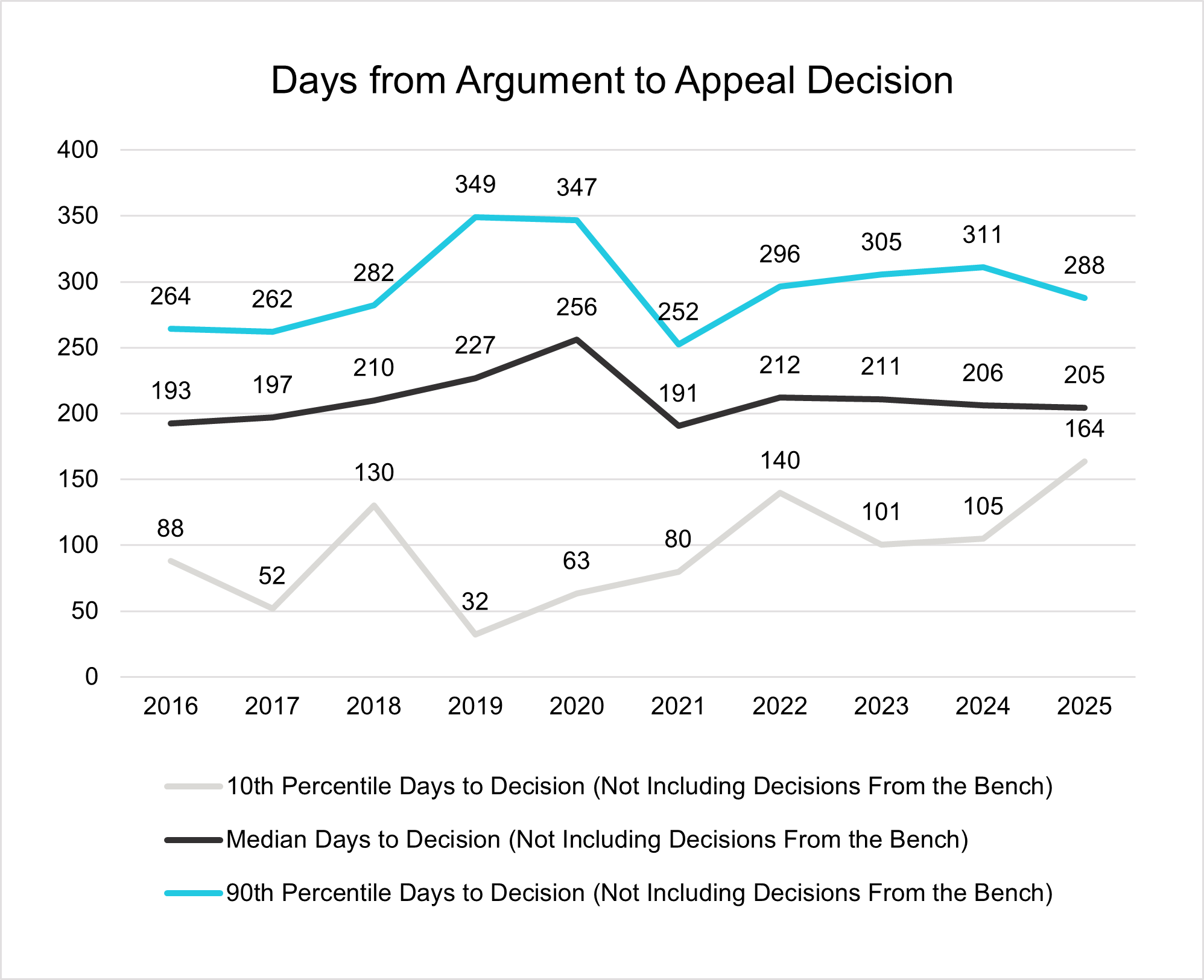

6. Decision Times Remain Stable

Excluding bench decisions, the median time from hearing to decision in 2025 was 205 days, just under seven months. The overall distribution was tight:

- 10% of cases were decided within 164 days (~5 months)

- 90% of cases were decided within 288 days (~9½ months)

Apart from the pandemic spike in 2020, this is almost exactly where the Court has sat for years.

The Bottom Line

Compared to recent historical benchmarks, the 2025 Supreme Court of Canada:

- Heard relatively few cases

- Continued to hear a significant number of as-of-right cases

- Made relatively more decisions from the bench

- Was relatively divided

- Was more criminal-law-heavy than at any point in the past decade

These are not just statistical curiosities. They shape what kinds of law the Court makes.